The Mind of a Hungry Ghost

Rebirth and ADHD

The first book of instruction in Aleister Crowley’s system of ritual magick is Liber O. In the introduction, he wrote: “In this book it is spoken of the Sephiroth and the Paths; of Spirits and Conjurations; of Gods, Spheres, Planes, and many other things which may or may not exist. It is immaterial whether these exist or not. By doing certain things, certain results will follow; students are most earnestly warned against attributing objective reality or philosophic validity to any of them.” I first read this in my final teen year, and it sunk deep. It has long been the approach I take with the more unverifiable aspects to the religious and spiritual teachings I follow. I remain agnostic but still employ them as a helpful way for framing my understanding of the world and my spiritual path. That is, I do not believe the “woo” things, but I entertain them as possibilities and use them as a framework for approaching my experience. With this preface, I can give the topic of today’s post. Among my DSM-V-TR diagnoses is ADHD, and I have given some thought to it, and the nature of greed and rebirth. If the reader will indulge me, I will share those thoughts.

We create our world through our intentions. I don’t say this as a way to victim-blame, but our past choices led us to where we are, and our present choices will lead us to where we go next.[1] This goes far deeper than most people realize, I think; when I say “create our world” I mean that the cognitive processes that construct our very perceptions result from what we have done and thought about in our past. The very structure of our minds is built up from our history of actions, and it is this structure that interprets and understands the world of our senses. What we think, and how we see things, come out of our past experiences.

This is the process that fuels our rebirth, too. We keep coming back to the Wandering (the literal translation of saṃsāra) because we want to. We are drawn to it. Whatever consciousness exists in the bardos, the realms in between one death and next birth, there is a decision to return because that consciousness wants something, or perhaps is afraid of what it would mean not to come back. And just as in life, the decisions are made according to the motivations that have been most pronounced in that karmic stream. They could be motivated by greed, hate, and delusion, or by generosity, love, and wisdom.

Greed, hate, and delusion are called the “three unwholesome roots” in the early texts and in Theravāda, and the “three poisons” in Mahāyāna. An observation made in later Theravādin tradition is that a person is usually dominated by one of those three roots, with a typology built around that. There are greed-types, hate-types, and delusion-types. These three words—greed, hatred, and delusion—are technical terms for broad movements that occur within the mind. Someone motivated by “greed” isn’t necessarily motivated by acquiring material wealth or power, but can also be greedy for sensual pleasures or other intangibles. (I am a greed-type, and an example of one who doesn’t have much interest in material wealth and is averse to the idea of having power, but is driven by a desire for pleasure.) Someone motivated by “hate” in this broad sense isn’t necessarily a hateful person. They are someone who tends to look at the negatives, at the downsides of their experiences, and to find faults in themselves and others. A delusion-type is someone who just doesn’t particularly care either way and just kind of floats through life with a significant degree of obliviousness. One example I have heard for understanding how the three types operate is to consider one going into an empty lecture hall. The greed-type will try to find the best seat (another thing I have always done!), the hate-type will try to avoid the worst seat, and the delusion-type doesn’t care where they sit.

These three types correspond to the three “lower” destinations for rebirth. A hate-type will be reborn in a hell. A delusion-type will be reborn as an animal. And a greed-type will be reborn as a hungry ghost.

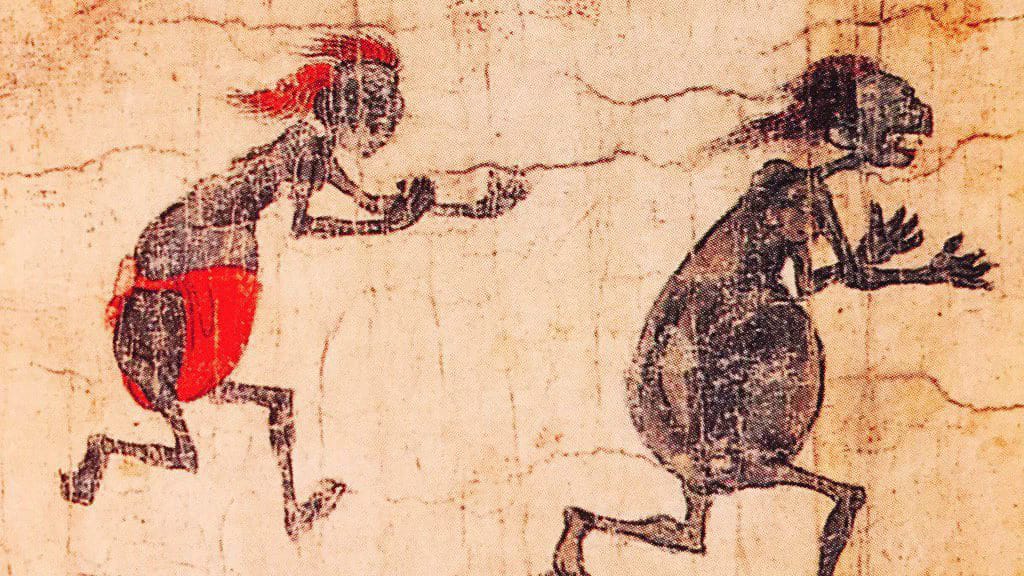

Hungry ghosts are appetite personified. One common representation of their bodies is that they have giant bellies, but very thin necks and mouths. No matter how much they eat, their hunger can never be sated. All they can do is consume endlessly with no satisfaction possible. They are pure desire.

So, then, what about ADHD?

At its core, ADHD is a deficiency in our dopamine systems. This is the molecule that provides us with motivation, pressing us to seek out pleasurable experiences. And further, it is the neurotransmitter critical for forming habits (a thing ADHDers constantly struggle with and often just can’t do deliberately). Those with an adequate baseline of dopamine are better able to engage in deferred gratification, or find more subtle rewards than those of us lacking, thus making the effort necessary to establish good habits more difficult for us.

While the name “ADHD”—attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—frames our phenotype as having a deficit of attention, this is a misrepresentation. That’s not the deficit. We can have very intense and sustained attention if we’re interested in something, or in a panic because of an approaching deadline. It’s a deficit in the regulation of attention. We have trouble controlling where our attention goes or how long it stays. Many of the most effective productivity strategies for an ADHD brain involve finding ways to manage our brains in such a way that they become interested in the things we need them to be interested in, so that we can live a functional life in our current society. Trying to force our attention to be on what is important instead of what is interesting when they don’t overlap can be physically painful at times. We have interest-based nervous systems, not importance-based ones.

The core problem of a dopamine deficiency translates to our experience as a core problem of chronic understimulation. We don’t have enough of the rewarding brain juice that makes planning and deferred gratification possible, and we are driven to boost it through extrinsic sources. This usually involves quick and easy ways of getting that boost, but almost all of those quick and easy ways are also detrimental to our well-being. Thus an ADHDer who can’t manage to finish a sentence in a conversation without jumping to a new topic is also able to spend ten hours grinding at a video game without even realizing they need to eat or use the toilet. Indeed, a lot of the aforementioned ADHD productivity strategies are ways of working with this need for a dopamine boost in a way that provides a sustained elevation (e.g., cold showers or exercise), rather than a quick burst that evaporates just as quickly (e.g., getting likes on social media).

So we have chronic understimulation driving us to seek out external sources of dopamine boosts, which, without intervention, will usually lead to us grabbing some quick but unhealthy option (a fact extensively manipulated by advertisers and developers of phone games nowadays). This is the mind of a hungry ghost. There is a fundamental hunger woven into the very structure of our brains that we must feed or our lives will fall apart.

When I entertain thoughts of the mechanics of rebirth, I wonder if the momentum of greed in my own karmic stream was not enough to send me to the hungry ghost realm. It was countered by some favorable tendencies in the karmic ensemble that enabled a human rebirth. But the greedy habit-energy was still there, and built me an ADHD brain. (Just to repeat, using these ideas about karma to victim-blame, to tell someone in a terrible situation it’s their fault for past actions, is an abuse of the ideas and not their purpose. Further, even taking the Buddha’s teachings on karma at face value, we simply can’t trace everything that happens to some past karma. That’s not how it works.)

How does this play into Dhamma practice, then? Well, I’m still navigating that.

I have mainly trained in the Thai Forest tradition, which puts a great deal of emphasis on “sense restraint.” This involves stepping back from habitually grabbing sensual pleasures in order to understand the mind’s relation to them, to the craving for them, and to the problems that craving them causes. The Buddha taught five basic ethical training rules[2] but gave the option for laity to take on extra renunciant training rules.[3. We are encouraged to take these extra rules on uposatha days,[4] or even longer if we want an intensified training period.

Early in my training, I could take these on without too much difficulty. I once managed to mostly keep them for the entire three-month period known as vassa, the “rains retreat” named for the rainy season in India, a period of intensified practice, (like a Buddhist Lent, except ours is about ninety days instead of forty!), with an average infraction of once a week. I can no longer do that, which is an entire other essay as to why. But lately when I try, a dark mood sets in, a depression-like state of sadness, anxiety, and lethargy. This is the result of an understimulated ADHD brain.

That left me with a few options. One was that I could continue with the deprivation. Could my brain rewire, grow accustomed to the reduced stimulation, perhaps even finding better stimulation simply through attentiveness and mindfulness? Or would I be locked into a sad fog and have to learn not to compound it with bad feelings, turning understimulation into suffering? The other is that I could go back to the sensory stimulation I found relief in before.

I personally know only one person, Venerable Pasanna, who is both advanced enough in their practice and knowledgeable enough about neurodivergence to give good advice on this point, and they advised feeding the dopamine-deficient brain stimulation when needed.

The real trick would be to find wholesome replacements. Instead of rewatching the same violent Avengers movie a hundred times (did I mention I’m autistic, too?), listen to Dhamma talks. Instead of songs about lust and sorrow, listen to chants of joy and peace. To keep up the stimulation, boosting that brain juice, but to do so through activities with more virtue than vice.

This is an ongoing task (one I could be more persistent at to be sure), as it involves retraining neural pathways that are reluctant to rewire (again, the autism), but it’s the general direction I am aiming for.

What about you? If you have ADHD, what is your experience with Dhamma or spiritual practice?

[1] To clarify, I am including the very act of identifying with something, with a feeling, or with some idea of who “I” am, as an intention. From my own experience working through my own trauma, the trauma results from painful things having happened to me, with the key idea being that there’s a me that things are happening to. One of the key aspects of the use of mindfulness meditation as a healing modality is untangling that, and learning that these painful experiences are not mine. Of course, this needs to be done in such a way that is not dissociation, but integrating into the whole psychic system, but that’s a whole other essay, and I hope the reader will overlook the deeper issues touched on here and forgive me for not elaborating on them.

[2] Don’t kill, don’t take what is not freely given (including cheating or fraud), don’t hurt yourself or others through sexual behaviors, don’t lie, and don’t get intoxicated.

[3] Eat only between the beginning of civil twilight and local noon, refrain from entertainment or making one’s appearance beautiful through cosmetics, jewelry, or fashionable clothing, refrain from luxurious seats or beds, and the rule of not harming yourself or others through sexual behaviors is changed to no engagement in any sexual activity whatsoever.

[4] Sort of a Buddhist sabbath that can be observed every quarter of the lunar cycle. A baseline for a devoted Buddhist is to observe them on full moon days. A more devoted Buddhist would observe them on both the new and the full moon days. An even more devoted Buddhist would add the first and third quarter moons.